How many times do we lower ourselves to the pavement or grass and pick up our dog’s, uh, business? Those of us who bother at all will likely perform this humble operation roughly 6,000 to 11,000 times, depending on the dog’s size and average lifespan. Not even counting the bad tummy days, that’s tending to a lot of business. When we scoop we’re also showing a whole heap of love for our four-legged companions, not to mention consideration for our two-footed neighbors who don’t appreciate stepping into unexpected surprises.

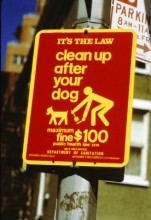

A new book shows where it all began. New York’s Poop Scoop Law: Dogs, the Dirt, and Due Process tells the story of how this custom, a normal part of daily life in many communities and central to dog ownership today, came about in the first place.

Even though it boggles the mind to think that poop scoop laws haven’t always existed, they weren’t handed down with the Ten Commandments. Collecting a dog’s mess by hand, instead of leaving it on the ground for someone else to watch out for, is a very recent idea, and this custom very nearly didn’t happen at all. New York wasn’t the first to come up with this bright idea. Other cities had already tried and given up on what seemed an impractical solution to a mounting urban problem when tough New Yorkers, never afraid to break the mold, decided to show the world that it could be done.

On this thirtieth anniversary of the first canine waste law to work in a major city, you can ask anyone who lived through the 1970s and they’ll tell you that sidewalks and parks in the Big Apple were obstacle courses for humans and dogs alike. The smell was overwhelming, especially on hot summer days. Public health was a concern, and the safety of small of children who played where dogs went. The elderly slipped and fell in the stuff. Nightclubbers were sick and tired of scraping off their platform shoes before trying to get into Studio 54. New York dogs were dropping an estimated 500,000 pounds of feces on city surfaces each and every day—and no one could agree on what to do with it! A few oddballs tried scooping but their neighbors looked at them like they were crazy. Everyone agreed that something had to be done to clean up New York City. But the question of what, exactly, that was became one of the hottest political issues of its time.

How did New Yorkers, who don’t like being told what to do, manage to convince each other that picking up a dog’s doo was a good thing to do?

New York’s Poop Scoop Law illustrates in humorous detail how much times have really changed since the seventies. What today seems a simple and straightforward request was in fact terribly controversial and complicated. Just passing the law seemed to take forever. For nearly a decade, New York’s City Council, whose job it is to create local laws, dodged the proposal because supporting it was too dangerous politically. Lawmakers, mayors, and politicians of all kinds were warned that if they dared to take a stand and say that keeping public areas clean was the duty of individual dog owners then they’d better not seek reelection. The majority of animal rights advocates, humane organizations, and pet owner groups all agreed that it was absurd and unfair to ask anyone but street cleaners to do the dirty deed, and they had many supporters, including the Brooklyn Cat Club. It took a no-nonsense mayor like Ed Koch to clear the air, and the sidewalks. Koch went out on a limb when he insisted that a poop scoop law would not be anti-dog but pro-New York. “I don’t care if it’s good luck to step in it,” he declared his first year in office. “I don’t want to.”

Taking this bold step for mankind meant changing perceptions and rethinking what it meant to be a responsible dog owner. Getting New Yorkers to obey the law once it was passed was a long and difficult process requiring everything from kind suggestions and polite hints to a vast public education campaign, no-nonsense peer pressure and vigilante tactics, even fistfights on the sidewalk before the strange, experimental idea became popular. After a few months of ugly encounters, Sanitation police were resigning because, they said, dog owners were verbally and physically abusive when confronted. The NYPD looked the other way at pet problems because getting involved was bad for community relations. Meanwhile, many dog owners were willing to try just about anything to avoid facing the terrifying task head-on. Some of them installed special doggy toilets inside their apartments. Others walked their pooches in cemeteries where they could be sure that no one was watching.

Thanks to several years of hard work and perseverance, scooping was transformed from a disgusting and humiliating thought into a decent, respectable act and a gesture of consideration toward fellow human beings. Some people started carrying designer bag dispensers with wrist attachments to make it more glamorous. New York’s City Club helped to make scooping less embarrassing by giving the annual award for Urban Design to the canine waste law in 1980. Of course, no law ever works 100%, and it would be unrealistic and unfair to expect such a miracle. Even today some New Yorkers feel that helpful reminders are necessary. But they can’t deny that most dog people do clean up every single time. It’s the few lone litterers, and a couple of stray piles per city block, that make the vast majority of good dog owners look bad and send their neighbors running to senators demanding that fines be increased. Enforcement is always the biggest problem with poop scoop laws but occasionally someone is caught leaving the scene of a crime. A few years ago a Coney Island woman was observed by a city official tiptoeing away from her dog’s deposit. She thought that no one was watching but got stopped a few blocks away. Protesting strongly, she insisted she had every intention of returning to the spot with a plastic bag, eventually—it was just that her brother had been hit by a milk truck and she had to get to the morgue. She got a summons along the way.

The poop scoop law did more than help New Yorkers get along better. Once the walkways were clear, people could get on with their busy and exciting lives and the rest of the world could follow in their footsteps. Because of canine waste laws, dog ownership, once considered the bad habit of a few anti-social misfits, has became socially acceptable in most places.

Since New York proved that it could be done, many other cities have started scooping while some are still holding back. Paris finally decided, only as recently as 2002, to hold dog owners accountable for their pets’ leavings, and while the final results still aren’t in, there has been some improvement on the Champs-Elysées. London, too, has put its foot down on “dog fouling” with stricter fines and even bans on dogs in some areas. Tarragona in Spain hired a special unit of doo-doo detectives who were instructed to film dog owners walking away from the problem and then using this as evidence in court. Lyon in France tried a publicity stunt by planting 10,000 pieces of fake plastic poop to increase public awareness—as though they didn’t have enough of the real kind. Other cities like Dresden, Vienna, and Edinburgh have seriously considered installing DNA databases that would identify dogs by their droppings and send police officers knocking on doors—but so far these plans are just too expensive. Typically, dog owners are not amused by any of these crackdowns and one Montrealer tried to sue that city for all the bad press he got after allegedly flinging unbagged feces at the poop police.

Closer to home, dog owners in American communities have, for the most part, cheerfully complied with local ordinances. Poop scoop laws have been well-received but some people are never happy and the occasional accident isn’t pretty. Fox Point, Wisconsin, says that forgetting a pooper-scooper is no excuse for failing to clean up after Fido. According to the local law, anyone with a leash must also have a plastic bag or some other device on their person at all times or be subject to a fine. In Plattsburgh, New York, the local historian drives around with used bread bags in the backseat of his car and offers them to any dog owners unprepared to handle their pets’ baguettes.

Miami Beach has decided to install special pet stations with free bag dispensers and to provide more trash cans on the sidewalks. Park rangers in Boulder, Colorado, are frustrated with hiking dog owners and have been sweeping the forests—not to clean up the mess but to stake hundreds of mounds of dog-doo with bright-blue flags designed to draw attention to the problem and make the guilty parties feel ashamed. San Diego, Arlington, Boise, Burlington, and Clearwater, Florida are all concerned that feces may be polluting the waterways. In Seattle there’s a $54 fine for not picking up in public places and a $109 penalty for leaving your dog’s mess on your own property for more than 24 hours.

Those trend-setting New Yorkers who started this whole thing in the first place are taking the lead once more by raising their minimum fine from $100 to a whopping $250 (with a maximum penalty of $1000 for repeat offenders). It seems that as dog ownership becomes more popular each year, the city also has more dogs and there’s a better chance that a few people might “forget” to bring their plastic bags.

But whether we’re out walking a dog on the streets of big cities like New York, Chicago, London or Paris, on the beaches of California, or down the road on our neighbor’s front lawn, it’s important to remember that picking up is about so much more than having neat and tidy surfaces. We may not get caught leaving the scene of a crime but we can be pretty sure that someone will eventually make a faux pas. Dogs and their caretakers already have enough enemies, and we don’t want to give the dog-haters more fuel. While San Francisco recycles canine waste into methane gas to save on energy, the rest of us can do our small part by showing that it’s alright to allow dogs in apartment buildings because their owners will act responsibly. Good behavior gives us more bargaining power when asking local authorities to open dog parks, or to improve conditions in city animal shelters.

Most important, by lowering ourselves in public we’re showing the world that we love our dogs enough to do just about anything to keep them.

For the Best that Pet Lifestyle has to offer follow Wendy Diamond on Facebook, Twitter, and right here at AnimalFair.com!