Animal Fair looks at the amazing life of legendary animal photographer Ylla, almost fifty years after her untimely death in India.

One of the last things Pryor Dodge sees on his way out of his apartment is the picture of his godmother which hangs by the door. In the black and white photo, a woman is standing in the wilderness, at a clearing in dense foliage, a river running through a gorge in the

background. In one hand, she holds a floppy canvas hat, which matches her loose fitting khaki pants. Her other hand brushes back her hair. She narrows her eyes against bright sunlight, but still smiles a wide, easy grin.

This smile is a striking feature in a movie star face. It’s an expression that, along with the safari clothes and the jungle backdrop, strongly reminds me of Katherine Hepburn in The African Queen. Both share the high cheekbones and beaming cheeriness which defined the golden-age generation of starlets. However, while the godmother has Hollywood looks, any description of her as a “starlet” ends with her rumpled, slept-in looking clothes. She has a toughness about her which fills her smile with strength. In African Queen terms, there’s some Bogie mixed in with the Hepburn.

Pryor’s godmother’s name was Ylla (pronounced “EE-la”), just one word, and she was a photographer. This picture of her, he tells me, was taken while she was on assignment in Africa a few years before her death in 1955. She died after falling from a moving jeep in India while photographing a bullock cart-race as the Maharajah’s guest. She had no family of her own, and so left her estate, including all her photographs, to Pryor, her best friend’s son.

Ylla made a wise choice in heirs. Pryor is a natural collector. Carefully mounted prints of and by Ylla adorn the walls of his apartment, which he complains doesn’t have enough space to properly store his collections. In addition to his godmother’s photos, Pryor has a huge number of artifacts relating to the history of the bicycle. These include old ads, lithographs, books, and several antique bikes with wooden frames or hugely oversized wheels. We sit down at a hand-hewn wood table, and Pryor begins to distribute Ylla’s photos across its uneven surface.

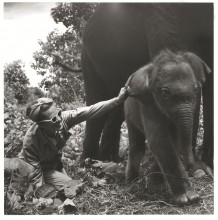

The picture of Ylla in Africa is one of the few in which animals do not appear. She was a legendary wildlife photojournalist and animal portraitist, and one of the best-known photographers of her time.

“If she were alive today, the whole world would know who she is,” Pryor tells me. “She wasn’t the type of person who simply disappears.”

Because she was a certain type of person, Ylla could infuse animal photography with wit, elegance and style. Throughout her life, she could make herself the talk of the town. Whether working, studying, and playing with painters, poets and photographers as part of left-bank life in Paris, or suffering a ferocious Panda bear attack at the Bronx zoo, or adventuring in the wildernesses of Kenya and India, Ylla was a minor celebrity and a prolific and respected artist. “She had a very turbulent childhood,” Pryor says.

Born Camilla Koffler in 1911 in Vienna, she experienced trauma early on when her Hungarian father and her Serbian mother divorced near the beginning of World War I. The war soon uprooted young Camilla and her mother from their already hurt home. The fighting made refugees of the pair, thrusting them into the tangled mess of shifting borders Central Europe had become. Ylla’s mother traveled through this turmoil with jewelry sewn into the lining of her dress. Circumstances forced mother and daughter apart, and Ylla, then six, spent long, lonely periods of time in a Budapest boarding school or in Belgrade with her mother’s relatives. These periods of isolation and separation profoundly affected the young girl, planting a seed in her which grew into a fierce self reliance.

While staying in Belgrade with an aunt, uncle, and cousins, Camilla started showing a fascination with animals. Cousins remember her going out into the street to play and returning home with stray dogs and cats. She felt sorry for them, and would always try to find them a permanent home. “I think Ylla herself felt like a stray because her mother had to let go of her more than once and put her somewhere,” muses Pryor.

After the war, in 1925, Camilla began studying in Belgrade to become a sculptor. She showed talent, and studied with an Italian artist, Palavicini. In 1929, a movie theater commissioned her to do a series of bas-reliefs for its box seats, and the eighteen year-old created panels depicting woodland creatures. Along with her first commission, animals were involved in another important step in the young artist’s development. Camilla found her given name means “camel” in Serbian, and so shortened it to the two-syllable moniker, Ylla. In more ways than one, animals were already helping Ylla make a name for herself.

In 1931, Ylla took the natural next step for anyone with artistic ambitions; she moved to Paris. At the time, the city was the world center of modernism with a thriving expatriate community. Left bank American writers like Ernest Hemmingway, Gertrude Stein, and Henry Miller all flocked there in droves to live cheaply. Pablo Picasso painted there, Jean Cocteau made experimental films, while James Joyce finished his epic novel, Ulysses.

Photography, originally invented by the French in 1827, was flourishing as a vital part of Paris’ avant garde. American Man Ray did portraits of many famous artists and practiced “Rayography,” printing object shadows directly onto paper, while Hungarian Andre Kertesz studied visual distortion with mirrors, and Romanian Brassaï recorded haunting surrealist images of teeming, seedy nightlife in the City of Lights.

Ylla had no intention of becoming a photographer. When she arrived in Paris, she started studying sculpture at the Collarossi Academy and worked as a photo retoucher to support herself. Ylla, quickly became friends with the woman she worked for, photographer Ergy Landau. Landau showed Ylla how to use a camera, and Ylla showed Landau her first pictures.

Ylla was intrigued by the new medium, and her budding interest clicked with her fascination with animals when she took a trip to Normandy. She stayed with friends and each morning walked their dogs through the surrounding farmland, taking her camera with her. She returned to Paris with pictures of sheep and cows which displayed a keen eye for the details of animal expression. When Landau saw these pictures, she was so impressed she immediately got them into a show at Paris’ Gallery de la Pleiade. With this, Ylla’s career began.

Another important thing happened in Paris in the early thirties: Ylla met and became friends with Pryor Dodge’s mother. Lyena Barjanskaya was there as a dress designer, and knew many of the same people as Ylla, including many photographers, such as Bill Brandt. Lyena modeled for Brandt while the English photographer was still learning to use a camera. Lyena let her dog model for Ylla.

Ylla was a dynamic presence on the Paris scene. Pryor describes his godmother as “strong, defiant, outgoing, and charming.” She was someone, he says, who “could get whatever she wanted, and meet whoever she wanted.” No matter where she dined, she would always sit down at the best seat at the best table. With such a personality, Ylla must have naturally gravitated to the great photo agent, Charles Rado.

In the early 30s, Charles Rado was a Hungarian in Paris who wanted to represent the best photographic talent with his newly formed Agence Rapho. He succeeded, and Rapho remains one of the world’s most prestigious photo agencies. Andre Kertesz, Brassaï, Bill Brandt, and Ergy Landau all signed on. As did Ylla, and soon became one of the agency’s star photographers.

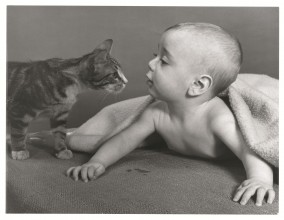

Rado helped Ylla get business for her newly opened pet portrait studio. He helped her bring out her first book of dog and cat portraits, Petites and Grands/ Big and Little. He also connected her with British zoologist Julian Huxley, who used her perceptive, expressive zoo portraits as illustrations for his book, Animal Language.

When the Second World War broke out, Rado, along with the Museum of Modern Art, helped Ylla get out of Europe and come to New York. There, she opened another pet portrait studio near Rockafeller Center, and became a regular at the Bronx zoo. Rado deftly crafted a public persona for her, making sure, for instance, incidents like the Panda bear attack and Ylla’s subsequent hospitalization were well reported.

Most importantly, Rado worked tirelessly to get Ylla published. He got her pictures into all the big magazines of the day: Look, Parade, True, McCalls, Madamoiselle, and Life, to name some. He also sent her on international assignments. He brought out Dogs and then Cats, both collections of pet portraits from her New York studio, as well as books using her zoo pictures and children’s books using shots from both the wild and around her own house. Famous writers such as French poet Jacques Prevert, Nicholo Tucci, and Margaret Wise Brown wrote text for these books.

Before her trip to Africa, Ylla photographed either domestic animals or animals in captivity. She had no pets of her own. However, at various times and in various combinations, dogs, cats, mice, squirrels, bear cubs, lion cubs, and ducks all stayed in her apartment as models. Then came Africa.

“Between Africa and India, [Ylla] got a real taste for the wild,” says Pryor. Traveling around Kenya, she found herself shooting the real thing, and she loved it. Her visual connection with the creatures of the Savannah was as strong and immediate as her connection to the French farmyard animals she had photographed almost twenty years earlier. A picture of her from Africa shows her proudly posing beside a rhinoceros, smiling that undaunted smile, as if the hulking animal were no more than a complacent milk cow.

Ylla returned to New York obsessed with shooting in nature. Her work took a different direction, moving out of the studio and zoo and into the outdoors. For the pictures in the children’s classic Two Little Bears, she followed a mother bear and her cubs through the wild, an anything-but-cutesy undertaking for one of her more cutesy projects.

After Africa, Ylla and Rado immediately started planning what would prove to be a fateful trip to India. Among those who encouraged her in this was the legendary French director Jean Renoir. She mailed a copy of her new book, Animals in Africa, to the Maharajah of Mysore, a lover of photography and wildlife, who quickly sent her an invitation. Though she didn’t return, this trip was the high point of Ylla’s career.

“Ylla was just in love with India. Maybe it’s best that’s where she did die,” Pryor says. Ylla spent seven months photographing India. She documented wildlife and spent time with royalty. She photographed Prime Minister Nehru with a lion cub, and met his daughter Indira, who would later become India’s Prime Minister. Famous Indian journalist Suresh Vaidya accompanied Ylla on many of her forays. A member of a lower caste than the Maharajah, his presence caused a slight stir, but strong-willed Ylla stuck with her friend. Other notables who traveled with her included Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s son Dennis, and Maltese Falcon director John Huston, who went on a tiger hunt and posed with Ylla and a dead tiger. (She wasn’t happy about [the dead animal],” Pryor adds. “But then she was the guest.”) Ylla photographed Huston as well, but only in the presence of live animals.

Ylla died photographing a water buffalo-drawn cart race at a county fair in Bharatpur, tumbling from the back of a jeep as it bounced along a bumpy dirt road. Suresh Vaidya, who was present at her death, wrote Charles Rado a ten page letter lamenting her passing. Newspapers and magazines all over the world published articles about the well-known animal photographer. The headline in the French magazine Point De Vue read simply “Ylla N’est Plus”: Ylla is no more. Others represented her adventuresome life in memorial comic strips.

“A number of people who knew her said she wasn’t the kind of person who wanted to get old and become infirm like everybody else,” recalls Pryor. “She died full of life, and that’s how she’s remembered.”

Charles Rado died in the early seventies, after steadfastly continuing to promote Ylla’s photographs. He brought out ten more books which used her work, including Animals in India.

A few year’s before Rado’s death, the Chinese gave then-president Nixon a Panda bear as a token of goodwill between nations. Rado provided The New York Times with Ylla’s pictures of the Panda which had attacked her decades earlier in the Bronx zoo. Times editors used one of these pictures for the front page story on the goodwill bear, finding in Ylla’s photographs a much surer depiction than any current pictures of the Nixon Panda.

Pryor Dodge was five years old when Ylla died. He has no memories of the woman herself, just one of him sitting on a bed, playing with a camera case he thinks belonged to her. Around the time Rado died, Pryor turned twenty-one and gained control of Ylla’s archive. For many years he has been researching the photographer who took pictures of him as a baby, but who he never really knew. Ylla’s pictures still appear in calendars, and the Japanese edition of The Two Little Bears is the eleventh language for that book. However, Pryor hopes the pictures she took will gain a wider audience, and more people will learn about the life she lived. He’s planning an exhibition and a monograph to go with it, both showing her work and life together.

What else would Ylla have done, had she lived? Pryor imagines her being around for the opening up of new possibilities, such as underwater photography. “What she would have discovered down there, the whole life of fish… she would have gone nuts with that! She would have spent a lot of time going around to the greatest places in the world to see underwater life. No doubt about that. Or mosquitoes and micro-organisms… who knows what she would have done with that?”

Writing in the introduction to her 1950 book, Animals, Ylla seems to agree with her godson:

“I wish that a fairy would wave a wand and transport me, for a month, into the animal world, in which, each night or day for that whole magic month, I would be in a different creature- a tiger, a fish, a bird, an insect. I would see the world of these creatures exactly as they see it. I would think their thoughts, feel their feelings, fight their battles, and understand their language. I would live their joys and fears and their satisfactions. And then I would return to my human self and my human life, remembering with my human mind all that I have see, thought and felt. If this experience were possible to me, I think I would then be possessed of the beginnings of a real understanding of life.”

For the Best that Pet Lifestyle and Animal Welfare has to offer follow Wendy Diamond on Facebook, Twitter, and right here at AnimalFair.com!